Music is all about movement. The beat. The stuff that makes you tap your foot or pencil on imaginary drums. Piano music has rhythm, and loads of it.

Let’s see how the rhythm is directed by the musical score.

The musical score is written by a composer, who decides what a song is going to sound like.

Let’s take a simple score you probably already know: “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star.”

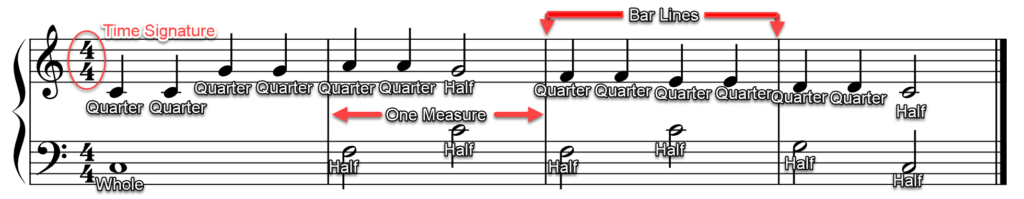

The treble clef contains notes that mainly solid black with stems, except for two notes that are not solid black.

The bass clef contains a larger hollow note at the beginning, and al the notes with stems are hollow.

The solid black notes are “quarter notes.” The hollow notes are “half notes.” And the first “fat” note in the bass clef is a “whole note.”

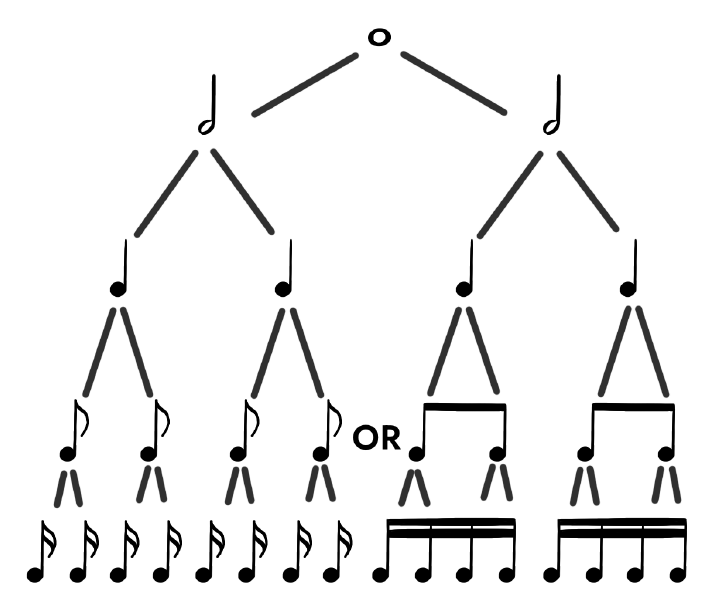

A whole note is held for 4 beats.

A half note is held for 2 beats.

A quarter note is held for 1 beat.

An eighth note is held for a half beat.

A sixteenth note is held for a quarter beat.

You can see how each time we step down to a smaller note, we are cutting in half the time we hold that note. There’s a graphic below that shows this relationship.

Let’s look at the time signature. The 4/4 that you see in the treble clef, next to the stylized G symbol, is the time signature.

A time signature tells us something about the rhythm, or beat, of the score. The top number 4 informs us that there are 4 beats per measure. The bottom 4 tells us that a quarter note gets one beat.

A “measure” is the space between the vertical bars in a score. It contains the notes, rests, and other “punctuation marks” that live within the measure. There may be as few as one measure in a song, or as many as thousands of measures.

There are 4 quarters in a whole dollar, right? In music, there are 4 quarter notes in a measure that contains 4 beats per measure.

In the Twinkle score, you can see 4 quarter notes in the first measure, two quarter notes and a half note in the second measure. By now you should be able to decipher the timing value of notes based on their type.

I’ve added the details written above, to this graphic. This is “musical score anatomy” and you’ll catch on very fast to this.

We use quarter notes, half notes, and whole notes primarily in contemporary music.

There are other helpers that we use to tell us how a rhythm should sound, or should be played.

A dot after a note means we extend that note for a half beat more. So a quarter note with a dot would get one-and-a-half beats. Below is what a dotted quarter note looks like:

Below is how the computer plays Twinkle Twinkle with a whole note, quarter notes and half notes. Listen to the difference a small note change makes when you compare the first and second Twinkles.

Now listen to the score below. I’ve added a dotted quarter note, followed by an eighth note, so I still maintain my 4 beats per measure. Feel the difference? The funny looking notes with the flags are 1/8 notes.

The dot after the first note means I hold the note for an extra half beat. The second note has a little flag on it, which means that note is held for a half beat shorter than a standard quarter note. Altogether, there are still 4 beats in the measure… just they rhythm changes. Listen.

You can see how music’s rhythm is determined by the various “punctuation” marks that are added, by note values, by time signature, and really, you can ignore all of this and play the song any way you choose.

All identifying features are there only because the composer wrote them that way, just as I wrote them in for this example, and to help you understand better how rhythm works.

Below is the hierarchy of notes and rests in graphical format, from the whole note at the top, to 1/16th notes at the bottom.

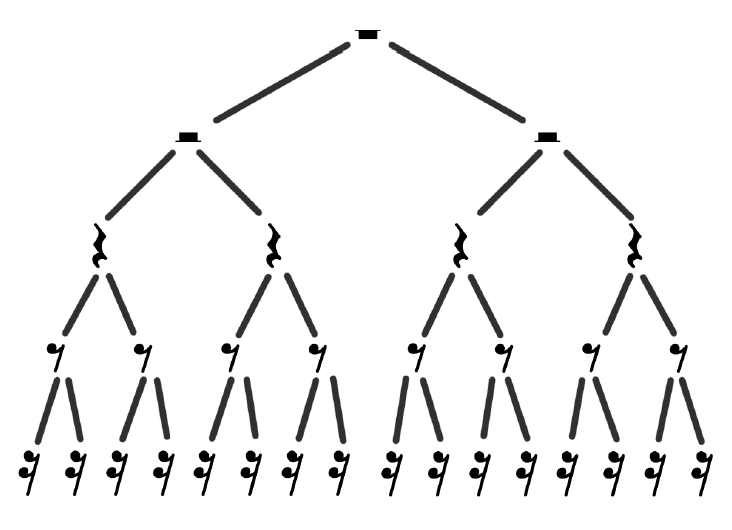

Below is the same graphic, except based on rests. For every note, there is a corresponding rest of the same value. The “upside down hat” at the top is a whole rest, and gets the same number of beats as a whole note.

There is much much more to music, but this good enough to get you moving along the path toward feeling like you’re making a difference in your own musical journey.

Now you know a little more how rhythm works, which is enough to get you playing the piano. The goal is not to learn at a cerebral level only, but to put these words into action.

Next, let’s look at the foundation of all Western music. That just happens to be the C Major scale.