Let’s figure out how chords are built, and discover their relationship with other notes.

A single note is easy to understand. It has no relationship to any other note when it is played alone.

But, when played in conjunction with another note, a relationship is begun. Let’s say we stack two notes – a C and an E. Now we have a duplet.

Let’s add a third note, G. Now we have a triplet. Three notes, each stacked one above the other. Or, one below the other.

The notes don’t care where they are stacked.

We can invert notes, so instead of having the C on the bottom of the stack, we put it on the top, and leave the E for the new bottom note. And keep repeating this cycle, moving the bottom note up to its next location on the keyboard.

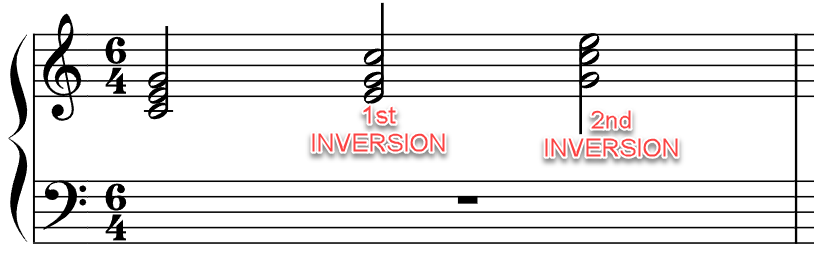

Below is a graphic of three chords, starting with middle C, in a 1-3-5 layout, or C, E, G. The next chord moves the C up one octave, leaving the E on the bottom. The last chord moves the previous bottom E up to the top, and the G is now the bottom note.

You can see how I’ve changed the time signature to 6/4 to allow room for three half-notes in a measure. If I kept the 4/4 time signature, there would only be room for two half-notes.

Remember that each measure can only contain a specific number of note and rest values that add up to that measure’s time. We can change the time signature on any measure we choose.

Chords can be built however you choose. The key is to listen as you build them, and keep their structure within the key signature you are working with. In this case, I am working with C Major, because it’s easier to understand in the beginning.

Below are the aforementioned chords being played by the computer. Listen to the relationship in sound. They all fit together and sound like they’re from the same family, because they are. These are all from the C Major scale, so they sound unified when played simultaneously.

Final note. See how the time signature starts with 6/4, then changes to 8/4? I added the 8/4 time so I could get two whole-note chords into one measure. Each chord is 4 beats long. Two chords need 8 beats. You should be able to see how this works at this point.